Yves Saint Laurent is perhaps the most important fashion designer of the 20th century. Born in Algeria in 1936 to a prominent family, he enjoyed a very French way of life. At just the age of three his extreme sensitivity and eye for fashion became evident when he cried over his aunt going out in a dress he did not like. He was ridiculed at school for playing with paper dolls and swore he would become famous because of this. And he certainly did. After winning various prizes in international design competitions, Yves was hired by Christian Dior in 1955 as a design assistant. Just two years later Christian Dior unexpectedly died and Yves was made chief designer of the Paris couture house at the incredibly young age of 21. His first collection “Trapeze Line” received fantastic reviews though after this his designs caused little excitement and were poorly received. In 1960 he was conscripted into the French army from which he as soon discharged after a nervous breakdown. When he returned to Paris, his position at Christian Dior was gone. With the help of Pierre Berge, who would become his lifelong partner, he sued Christian Dior over the matter and used the money won in the lawsuit to help establish Yves’ own couture house. His first show received mixed reviews though he did soon receive an important backer, the powerful cosmetics company Charles of the Ritz. In this year, 1965, for his fall collection Yves created the dresses that launched him to international celebrity status, inspired by the Dutch painter Mondrian.

Mondrian was an abstract painter whose famous works of the 1920s used a limited color pallet of black, white, red, yellow, and blue. These colors were used in greatly simplified abstract forms in an attempt to create some sort of fundamental order present in the visual world. He died in 1944 and so did not see what was dubbed most often as “The Mondrian Look” designed by Yves. Yves though was not the first to use inspiration from Mondrian even in the world of fashion. Years earlier Anne Klein had created similar pieces for Junior Sophisticates and a sweater company, Studio Knits, had done the same but “no one was looking then.”[i] An important distinction and explanation for this is that Yves work premiered at a French couture show and not a shop window. However despite their success, the Mondrian dresses of Yves were conceived only a fortnight before the show and completed only four days before the show. In a worthwhile attempt to add innovation to what was previously a conventional collection, Yves decided to add this collection of simple wool jersey shifts. He based them on the paintings of Mondrian he had seen in a series of monographs given to him by his mother for Christmas which had struck him visually and intellectually. The incorporation of art in fashion was a relatively new idea and most prominently it had appeared the summer before with various pieces based off optical art, though these were not too well favored. The Mondrian dresses were refreshing, a designing masterpiece technically and conceptually since they were as flattering to the female form as they were reminiscent of the original flat oil paintings. Desperate for success after having disappointed the fashion world since his fantastic first show at Christian Dior, the Mondrian dresses secured him financially and to an extent emotionally.

The reception was astounding. The dresses themselves were applauded as soon as they appeared on August 2nd and the shy Yves, coaxed into giving a curtain call, received a standing ovation. Word of the fantastic line spread throughout Paris and the press, scheduled to see the show weeks later scrambled to interview private clients who had actually seen the collection. Pierre Berge, previously disenchanted with the press due to negative reviews, decided to move the press presentation to just four days after the debut show, something allowed by designers for the first time in this Paris show. Before this though, praise for Yves’ Mondrian dresses was already all over the media. French Voguefeatured a Mondrian dress on the cover of its September issue and Great Britain and the United States included spreads that same month as well, just a little over a month after its debut show. America quickly became infatuated with the Mondrian dresses as well and the New York Times couldn’t stop writing about them. Just a day after the debut show an article mainly focusing on Yves was published that not only praised the works despite the author having never seen them, it also described the “dress that drew the most raves” incorrectly as it said it incorporated a green square which was in fact red.[ii] An article published only a few days later, after the works were viewed by the press, now described the dress everyone wanted as “white with a bright blue block high on one shoulder, a bigger red patch on half the torso, a yellow hem and four thick lines of black separating each color.”[iii] While the description in this case is accurate, this Mondrian dress, not the one described a few days before, became the iconic piece of the collection and the focus from this point forward. What the media said became true.

The praise was almost completely positive though one fashion editor thought that the Mondrian dresses “went nowhere” and a filmmaker was inspired by them to make a “spoof” of the fashion world.[iv] Yet the Mondrian dresses and Yves still “stole most of the couture honors in Paris this season” with his “brightest, freshest and best.”[v] Just 12 days after the debut show there was an article covering the many manufactures rushing to imitate the dresses at modest prices and two days after this there was already an ad in theNew York Times for one of these imitations after which countless others follow.[vi] On the imitations Yves said “It please me very much” and even bought several of them.[vii]Quickly everything became available in Mondrian from lingerie to handbags and it was made for everyone, from infants to grandmothers. The pieces were not controversial as while they were attractive, they were not sexy. Patterns were rampant for the Mondrian dresses; they were the most copied pieces in the world. But despite all this hype about the Mondrian dresses, the first image of one of Yves’ actual pieces (instead of a sketch or imitation) did not appear until the end of August.

The article that featured the image in the New York Times was prophetic as it says that “In addition to [the Mondrian dresses] being duplicated here, they are expected to have a long-range impact on fashion.”[viii] The dresses did accomplish this as they brought geometry into design but perhaps more importantly they gave youth an even greater prominence in fashion. This was noticed from day one as every article about the Mondrian dresses described their youth and gaiety, the “juvenile-looking styles that grown-up women want.”[ix] They fit seamlessly into the popular preexisting culture of Mod that focused on fashion and youth. While Yves did not comment specifically on the designs themselves he did say that “there is a new trend in fashion. It is young and strives for attractiveness rather than elegance.”[x] Another indication of this was the ready-to-wear boutiques opened by many couture designers that were aimed at the youth. Due to his Mondrian success, Yves was able to pursue this as well and accomplish it by only 1966 with a boutique called Rive Gauche or Left Bank, a name which indicated his association with the art of the past in Paris. Yves constantly said that he himself bought ready-to-wear and that he wanted people, regular people, to wear his designs.[xi] However while the New York Times may have fantasized that money was no factor for Yves, it could not have escaped the minds of his backers as these ready-to-wear boutiques were considerable money makers. Couture, custom made clothing, was only possible for the exceedingly rich and only a few pieces were created and sold. In ready-to-wear everything was mechanically produced and many pieces were manufactured and sold.

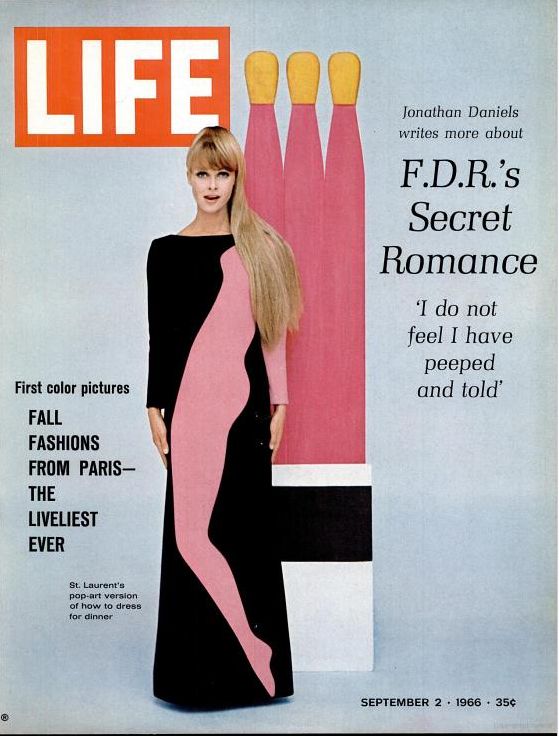

His backers, the powerful cosmetics company Charles of the Ritz, elevated his popularity and profited from it by also promoting his money making perfume in the United States at the same time as his Mondrian dress success. In October and November he toured six cities within which he mingled with the fashion, art, and theater worlds. Probably the most important thing to note about his visit was what he said and did in relation to art; “I would like to go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see the father of my dresses. A sentimental trip. We do not have many Mondrian paintings in Paris.”[xii] Soon following this Yves connection to the art world increased as he became friends with artists of the time, the most famous being Andy Warhol. In his fall collection of 1966 this influence was obvious as he created Pop Art dresses for the Paris couture show. These dresses with large pop art style symbols on them, the most notable being a giant nude, were received with some enthusiasm by the youth in France but in America they were disliked. The New York Times which had praised Yves’ Mondrian dresses in many articles gave the Pop Art dresses attention in only one article with a scathing review which called the dresses “outdated,” suited for “a private joke,” and said they “don’t have a pop art look at all.”[xiii] However America seemed somewhat flattered by Yves’ tribute to pop art as the Nude Dress was featured on the cover of Life. These pop art dresses, while perhaps a falling short of expectations, still impacted the fashion world. The incorporation of popular images on clothing was previously unheard of and became an everyday item.

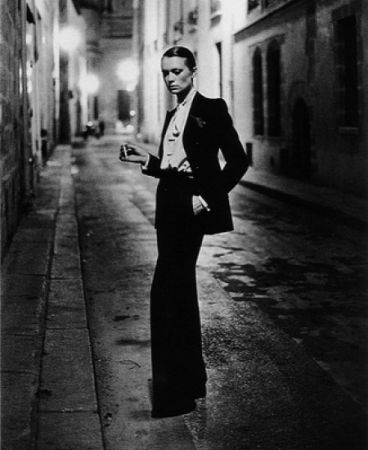

Both the Mondrian and Pop Art dresses showed the influence of art on Yves and his designs, a tradition he continued throughout his career. Articles written about Yves even those written after his obvious relationship with art during 1965-66, prominently spoke of the Mondrian dresses, though the Pop Art dresses remain forgotten, or ignored. The Mondrian dresses were always the iconic pieces thought of in association with Yves, despite his more important and controversial contributions to the world of fashion and society. Works like “le smoking,” a feminized men’s tuxedo made only one year after the Mondrian dresses, bent expected gender specific dress though its fame was not as instant. Mondrian was iconic before there ever were Mondrian dresses but perhaps more importantly the Mondrian dresses, unlike “le smoking” gave no indication of Yves homosexuality, something expected, though not discussed, in the world of fashion at this time. He and his lifelong partner amassed a large collection of art including several Mondrians and images of Yves painted by Andy Warhol. Many images and interviews with Yves and Pierre Berge took place in front of works of art in their collection. Following Yves death in 2008 Pierre Berge decided to auction off what was described as one of the great art collections of modern times. However, he could not part with the Andy Warhol images of Yves.

In 2009 a show entitled “The Great World of Andy Warhol” at the Grand Palais in Paris opened that intended to use all of his portraits, including those of Yves Saint Laurent. However his partner Pierre Berge pulled the pieces from the exhibit outraged that they were included in the glamour section and not in their rightful place, with the artists. Is fashion art? Regardless of the answer, fashion is indeed placed in the museum. Would you place the Mondrian dresses in modern art or costume? What about “le smoking”?

Bibliography

Rawsthorn, Alice. Yves Saint Laurent: a Biography. New York: Nan A. Talese, 1996.

Saint, Laurent Yves., and Diana Vreeland. Yves Saint Laurent. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983.

Saint, Laurent Yves, Marguerite Duras, and Richard Avedon. Yves Saint Laurent: Icons of Fashion Design. München: Schirmer/Mosel, 2010.

[i] Enid Nemy. “Everybody, Almost, Is in the Mondrian Race.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 20 Aug. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[ii] Gloria Emerson. “St. Laurent and Givenchy.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 3 Aug. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[iii] Gloria Emerson. “Saint Laurent: Bright, Fresh Clothes For a Baby-Faced Blonde.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 7 Aug. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[iv] Gloria Emerson. “Even the Lemons Glow Brightly In Gray Warsaw.” New York Times(1923-Current file) 14 Dec. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.; Gloria Emerson. “From Paris Comes a Film Spoof of the Fashion World.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 25 Nov. 1966, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[v] Gloria Emerson. “Yves Saint Laurent: Two Stars of Paris.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 15 Aug. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.; Gloria Emerson. “Saint Laurent: Bright, Fresh Clothes For a Baby-Faced Blonde.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 7 Aug. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[vi] Bernadine Morris. “Mondrian’s Art Used in Fashion.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 14 Aug. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[vii] Gloria Emerson. “St. Laurent’s U.S. Trip To Be ‘a Lot of Work’.” New York Times(1923-Current file) 22 Oct. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.; “Copies of St. Laurent Bought by St. Laurent.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 13 Nov. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[viii] “Summing Up Another Fashion Season in Paris.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 30 Aug. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[ix] Gloria Emerson. “St. Laurent and Givenchy.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 3 Aug. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[x] Julie Byrne. “Style Quiz Tailored for Yves: Style Quiz Tailored for Yves, So He Designs the Answers.” Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File) 1 Nov. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers Los Angeles Times (1881 - 1987), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Angela Taylor. “‘I Hate Mondrian Now,’ St. Laurent Says.” New York Times (1923-Current file) 12 Nov. 1965, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

[xiii] Gloria Emerson. “A Nude Dress That Isn’t: Saint Laurent: In a New, Mad Mood.”New York Times (1923-Current file) 5 Aug. 1966, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2007), ProQuest. Web. 10 Oct. 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment